♘امیرحسین♞

♘ مدیریت انجمن اسب ایران ♞

The Akhal-Teke, 'Ahalteke' in the Turkmen language, horse breed (pronounced /a.hal'tеk.je/) is a breed of horse from Turkmenistan, where they are a national emblem.They are noted for their speed and for endurance on long marches. These "golden-horses" are adapted to severe climatic conditions and are thought to be one of the oldest surviving horse breeds. There are currently about 3,500 Akhal-Tekes in the world, mostly in Turkmenistan and Russia, although they are also found in Germany and the United States. Many Akhal-Tekes are bred at the Tersk stud in the northern Caucasus Mountains.

Breed characteristics

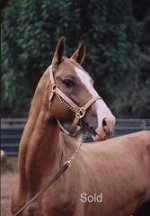

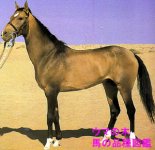

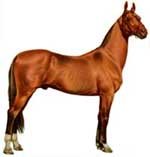

The Akhal-Teke usually stands between 14.3 and 16.3 hands. The horses are usually a pale golden color somewhat akin to buckskin, with black points. They can also be bay, black, chestnut, or grey. The Akhal-Teke's most notable and defining characteristic is the natural metallic bloom of its coat.This is especially seen in the palominos and buckskins, as well as the lighter bays, although some horses "shimmer" more than others. The color pattern thought to have been used as camouflage in the desert.

The Akhal-Teke has a fine head with a straight or slightly convex profile, and long ears. It also has almond-shaped eyes. The mane and tail is usually sparse. Their long back is lightly muscled, and is coupled to a flat croup and long, upright neck. The Akhal-Teke possesses a sloping shoulder and thin skin. These horses have strong, tough, but fine limbs. They have a rather slim body and ribcage (like an equine version of the greyhound), with a deep chest. The conformation is typical of horses bred for endurance over distance. The Akhal-Tekes are lively and alert, with a reputation for being "one-rider" horses.

The breed is tough and resilient, having adapted to the harshness of Turkmenistan lands, where horses must live without much food or water. This has also made the horses good for sport. The breed has great endurance, as shown in 1935 when a group of Turkmen horsemen rode the 2500 miles from Ashgabat to Moscow in a mere 84 days, including a three-day crossing of 235 miles of desert without water. The Akhal-Teke is also known for its form and grace as a show jumper.

Breed history

According to some, the Akhal-Teke were kept hidden by their tribesmen for years. The area where the breed first appeared, the Turkmenistan desert Kara Kum, is a rocky, flat desert surrounded by mountains. However, others claim that the horses are descendants of the mounts of Mongol raiders of the 13th and 14th century.

The breed is very similar to the now-extinct Turkoman Horse, once bred in neighboring Iran. Some historians believe that the two are different strains of the same breed. It is a disputed "chicken or egg" question if the influential Arabian was either the ancestor of the breed or was developed out of this breed. It is also probable that the so-called "hot blooded" breeds, the Arabian, Turkoman, Akhal-Teke and the Barb all developed from a single "oriental prototype" of wild predecessor (see Domestication of the horse, Four foundations theory)

Tribesmen of Turkmenistan first used the horses for raiding. They selectively bred the horses, keeping records of the pedigrees via an oral tradition. The horses were called "Argamaks" by the Russians, and were cherished by the nomads.

In 1881, Turkmenistan became part of the Russian Empire. The tribes fought with the tsar, eventually losing. A Russian general, Kuropatkin, who grew to love the horses he had seen while fighting the tribesmen, founded a breeding farm after the war and renamed the horses "Akhal-Tekes," after the Teke Turkmen tribe that lived near the Akhal oasis. The Russians printed the first studbook in 1941, which included 287 stallions and 468 mares.

The Akhal-Teke has had influence on many breeds, possibly including the Thoroughbred through the Byerly Turk (which may have been Akhal-Teke, an Arabian or a Turkoman Horse), one of the foundation stallions of the breed. The Trakehner has also been influenced by the Akhal-Teke, most notably by the stallion Turkmen-Atti, as has the Russian breeds Don, Budyonny, Karabair, and Karabakh.

The breed suffered greatly when the Soviet Union required horses to be slaughtered for meat, even though local Turkmen refused to eat it. At one point only 1,250 horses remained and export from the Soviet Union was banned. The government of Turkmenistan now uses the horses as diplomatic presents as well as auctioning a few to raise money for improved horse breeding programs. Male horses are not gelded in Central Asia.

In the early 20th century, crossing between the Thoroughbred and the Akhal-Teke took place, aiming to create a faster long-distance racehorse. However, the Anglo Akhal-Tekes were not as resilient as their Akhal-Teke ancestors, and many died due to the harsh conditions of Central Asia. The crossbreeding was ended in 1935, after the 2,600 mile endurance race from Ashkabad to Moscow, when the pure-breds finished in much better condition than the part-breds. The Thoroughbred cross is believed to have been so destructive to the breed that a horse with Thoroughbred ancestors must have 15 generations pass before it can be registered in the studbook. Since 1973, all foals must be blood-typed to be accepted in the stud book in order to protect the purity. A stallion not producing the right type of horse can be removed. The stud book was closed in 1975.

Uses of the Akhal-Teke

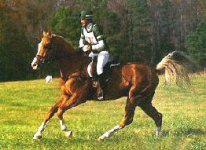

Because of the purity of the ancient breed, the Akhal-Teke has been used for developing new breeds, most recently the Nez Perce Horse (Appaloosa x Akhal-Teke). The Akhal-Teke, due to its natural athleticism, makes it a great sport horse, good at dressage, show jumping, eventing, racing, and endurance riding.

One such great sport horse was the Akhal-Teke stallion, Absent. He won the Prix de Dressage at the 1960 Olympics in Rome. He was eight years old, and ridden by Sergei Filatov. He went again with Filatov to win the bronze individual medal in Tokyo in the 1964 Olympics, and won the Soviet team gold medal under Ivan Kalita at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City

Breed characteristics

The Akhal-Teke usually stands between 14.3 and 16.3 hands. The horses are usually a pale golden color somewhat akin to buckskin, with black points. They can also be bay, black, chestnut, or grey. The Akhal-Teke's most notable and defining characteristic is the natural metallic bloom of its coat.This is especially seen in the palominos and buckskins, as well as the lighter bays, although some horses "shimmer" more than others. The color pattern thought to have been used as camouflage in the desert.

The Akhal-Teke has a fine head with a straight or slightly convex profile, and long ears. It also has almond-shaped eyes. The mane and tail is usually sparse. Their long back is lightly muscled, and is coupled to a flat croup and long, upright neck. The Akhal-Teke possesses a sloping shoulder and thin skin. These horses have strong, tough, but fine limbs. They have a rather slim body and ribcage (like an equine version of the greyhound), with a deep chest. The conformation is typical of horses bred for endurance over distance. The Akhal-Tekes are lively and alert, with a reputation for being "one-rider" horses.

The breed is tough and resilient, having adapted to the harshness of Turkmenistan lands, where horses must live without much food or water. This has also made the horses good for sport. The breed has great endurance, as shown in 1935 when a group of Turkmen horsemen rode the 2500 miles from Ashgabat to Moscow in a mere 84 days, including a three-day crossing of 235 miles of desert without water. The Akhal-Teke is also known for its form and grace as a show jumper.

Breed history

According to some, the Akhal-Teke were kept hidden by their tribesmen for years. The area where the breed first appeared, the Turkmenistan desert Kara Kum, is a rocky, flat desert surrounded by mountains. However, others claim that the horses are descendants of the mounts of Mongol raiders of the 13th and 14th century.

The breed is very similar to the now-extinct Turkoman Horse, once bred in neighboring Iran. Some historians believe that the two are different strains of the same breed. It is a disputed "chicken or egg" question if the influential Arabian was either the ancestor of the breed or was developed out of this breed. It is also probable that the so-called "hot blooded" breeds, the Arabian, Turkoman, Akhal-Teke and the Barb all developed from a single "oriental prototype" of wild predecessor (see Domestication of the horse, Four foundations theory)

Tribesmen of Turkmenistan first used the horses for raiding. They selectively bred the horses, keeping records of the pedigrees via an oral tradition. The horses were called "Argamaks" by the Russians, and were cherished by the nomads.

In 1881, Turkmenistan became part of the Russian Empire. The tribes fought with the tsar, eventually losing. A Russian general, Kuropatkin, who grew to love the horses he had seen while fighting the tribesmen, founded a breeding farm after the war and renamed the horses "Akhal-Tekes," after the Teke Turkmen tribe that lived near the Akhal oasis. The Russians printed the first studbook in 1941, which included 287 stallions and 468 mares.

The Akhal-Teke has had influence on many breeds, possibly including the Thoroughbred through the Byerly Turk (which may have been Akhal-Teke, an Arabian or a Turkoman Horse), one of the foundation stallions of the breed. The Trakehner has also been influenced by the Akhal-Teke, most notably by the stallion Turkmen-Atti, as has the Russian breeds Don, Budyonny, Karabair, and Karabakh.

The breed suffered greatly when the Soviet Union required horses to be slaughtered for meat, even though local Turkmen refused to eat it. At one point only 1,250 horses remained and export from the Soviet Union was banned. The government of Turkmenistan now uses the horses as diplomatic presents as well as auctioning a few to raise money for improved horse breeding programs. Male horses are not gelded in Central Asia.

In the early 20th century, crossing between the Thoroughbred and the Akhal-Teke took place, aiming to create a faster long-distance racehorse. However, the Anglo Akhal-Tekes were not as resilient as their Akhal-Teke ancestors, and many died due to the harsh conditions of Central Asia. The crossbreeding was ended in 1935, after the 2,600 mile endurance race from Ashkabad to Moscow, when the pure-breds finished in much better condition than the part-breds. The Thoroughbred cross is believed to have been so destructive to the breed that a horse with Thoroughbred ancestors must have 15 generations pass before it can be registered in the studbook. Since 1973, all foals must be blood-typed to be accepted in the stud book in order to protect the purity. A stallion not producing the right type of horse can be removed. The stud book was closed in 1975.

Uses of the Akhal-Teke

Because of the purity of the ancient breed, the Akhal-Teke has been used for developing new breeds, most recently the Nez Perce Horse (Appaloosa x Akhal-Teke). The Akhal-Teke, due to its natural athleticism, makes it a great sport horse, good at dressage, show jumping, eventing, racing, and endurance riding.

One such great sport horse was the Akhal-Teke stallion, Absent. He won the Prix de Dressage at the 1960 Olympics in Rome. He was eight years old, and ridden by Sergei Filatov. He went again with Filatov to win the bronze individual medal in Tokyo in the 1964 Olympics, and won the Soviet team gold medal under Ivan Kalita at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City