♘امیرحسین♞

♘ مدیریت انجمن اسب ایران ♞

began from the real life tasks of the vaqueros and cowboys of the Americas to gather up cattle for various purposes such as branding, moving them to new pastures, or to market. The term was also used to refer to the sport which arose out of the working practices of cattle ranching, and it is this latter usage which was adopted into the cowboy tradition of the United States and Canada.

While the concept of a Rodeo often conjures up Hollywood movie images of dusty cowboys in rural arenas, the modern professional rodeo is a very different sport. Its long season peaks on the July 4th weekend, but concludes with the world’s richest rodeo, the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) Wrangler National Finals Rodeo (NFR) in Las Vegas, Nevada in December.

The term rodeo was first used in English approximately 1834 to refer to a cattle round-up. it is derived from the Spanish word rodear, meaning to surround or go around, used to refer to "a pen for cattle at a fair or market," derived from the Latin rota or rotare, meaning to rotate or go around.

Events

Timed events

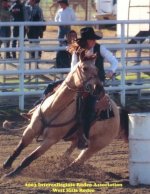

* Barrel racing and pole bending - the timed speed and agility events seen in rodeo as well as gymkhana or O-Mok-See competition. Both men and women compete in speed events at gymkhanas or O-Mok-Sees; however, at rodeos, barrel racing is an exclusively women's sport. In a barrel race, horse and rider gallop around a cloverleaf pattern of barrels, making agile turns without knocking the barrels over. In pole bending, horse and rider run the length of a line of six upright poles, turn sharply and weave through the poles, turn again and weave back, then return to the start.

* Steer wrestling - Also known as "Bulldogging," this is a rodeo event where the rider jumps off his horse onto a steer and 'wrestles' it to the ground by grabbing it by the horns. This is probably the single most physically dangerous event in rodeo for the cowboy, who runs a high risk of jumping off a running horse head first and missing the steer, or of having the thrown steer land on top of him, sometimes horns first.

* Goat tying - usually an event for women or pre-teen girls and boys, a goat is staked out while a mounted rider runs to the goat, dismounts, grabs the goat, throws it to the ground and ties it in the same manner as a calf. This event was designed to teach smaller or younger riders the basics of calf roping without the more complex need to also lasso the animal.

Roping

Roping encompasses a number of timed events that are based on the real-life tasks of a working cowboy, who often had to capture calves and adult cattle for branding, medical treatment and other purposes. A lasso or lariat is thrown over the head of a calf or the horns and heels of adult cattle, and the animal is secured in a fashion dictated by its size and age.

* Calf Roping, sometimes called Tie-down roping - A calf is roped around the neck by a lariat, the horse stops and sets back on the rope while the cowboy dismounts, runs to the calf, throws it to the ground and ties three feet together. (If the horse throws the calf, the cowboy must lose time waiting for the calf to get back to its feet so that the cowboy can do the work. The job of the horse is to hold the calf steady on the rope) This activity is still practiced on modern working ranches for branding, medical treatment, and so on.

* Team roping, also called "heading and heeling," is the only rodeo event where men and women riders may compete together. Two people capture and restrain a full-grown steer. One horse and rider, the "header," lassos a running steer's horns, while the other horse and rider, the "heeler," lassos the steer's two hind legs. Once the animal is captured, the riders face each other and lightly pull the steer between them, so that it loses its balance, thus in the real world allowing restraint for treatment.

* Breakaway roping - an easier form of calf roping where a very short lariat is used, tied lightly to the saddle horn with string and a flag. When the calf is roped, the horse stops, allowing the calf to run on, flagging the end of time when the string and flag breaks from the saddle. In the United States, this event is primarily for women of all ages and boys under 12, while in some nations where traditional calf roping is frowned upon, riders of both genders compete.

"Rough Stock" competition

In spite of popular myth, most modern "broncs" are not in fact wild horses, but are more commonly spoiled riding horses or horses bred specifically as bucking stock.

* Bronc riding - there are two divisions in rodeo, bareback bronc riding, where the rider is only allowed to hang onto a bucking horse with a surcingle, and saddle bronc riding, where the rider is allowed a specialized western saddle without a horn (for safety) and may hand onto a heavy lead rope attached to a halter on the horse.

* Bull Riding - an event where the cowboys ride full-grown bulls instead of horses, skills similar to bareback bronc riding are required. Rodeo clowns, now known as Bullfighters, word during bull riding competition to help prevent injury to fallen riders.

Early history of rodeo

Rodeo stresses its western folk hero image and its being a genuinely American creation. But in fact it grew out of the practices of Spanish ranchers and their Mexican ranch hands (vaqueros), a mixture of cattle wrangling and bull fighting that dates back to the sixteenth-century conquistadors.

One of the activities introduced by the Spanish and incorporated into rodeo was bull riding. Another was steer wrestling, involved wrestling the steer to the ground by riding up behind it, grabbing its tail, and twisting it to the ground. Bull wrestling had been part of an ancient tradition throughout the ancient Mediterranean world including Spain. The ancient Minoans of Crete practiced bull jumping, bull riding, and bull wrestling. Bull wrestling may have been one of the Olympic sports events of the ancient Greeks.

The events spread throughout the Kingdom of New Spain and was found at fairgrounds, racetracks, fiestas, and festivals in nineteenth century southwestern areas that now comprise the United States. However, unlike the roping, riding, and racing, this contest never attracted a following among Anglo cowboys or audiences. It is however a favorite event included in the charreada, the style of rodeo which originated in the Mexican state of Jalisco.

There would probably be no steer wrestling at all in American rodeo were it not for a black cowboy from Texas named Bill Pickett who devised his own unique method of bulldogging steers. He jumped from his horse to a steer’s back, bit its upper lip, and threw it to the ground by grabbing its horns. He performed at local central Texas fairs and rodeos and was discovered by an agent, who signed him on a tour of the West with his brothers. He received sensational national publicity with his bulldogging exhibition at the 1904 Cheyenne Frontier Days. This brought him a contract with the famous 101 Ranch Wild West, where he spent many years performing in the United States and abroad.

Pickett attracted many imitators who appeared at rodeos and Wild West shows, and soon there were enough practitioners for promoters to stage contests. The first woman bulldogger appeared in 1913, when the great champion trick and bronc rider and racer Tillie Baldwin exhibited the feat. However, women's bulldogging contests never materialized. But cowboys did take up the sport with enthusiasm but without the lip-biting, and when rodeo rules were codified, steer wrestling was among the standard contests. Two halls of fame recognize Bill Pickett as the sole inventor of bulldogging, the only rodeo event which can be attributed to a single individual.

Rodeo itself evolved after the Texas Revolution and the US-Mexican War when Anglo cowboys learned the skills, attire, vocabulary, and sports of the vaqueros. Ranch-versus-ranch contests gradually sprang up, as bronc riding, bull riding, and roping contests appeared at race tracks, fairgrounds, and festivals of all kinds. William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) created the first major rodeo and the first Wild West show in North Platte, Nebraska in 1882. Following this successful endeavor, Cody organized his touring Wild West show, leaving other entrepreneurs to create what became professional rodeo. Rodeos and Wild West shows enjoyed a parallel existence, employing many of the same stars, while capitalizing on the continuing allure of the mythic West. Women joined the Wild West and contest rodeo circuits in the 1890s and their participation grew as the activities spread geographically. Animal welfare groups began targeting rodeo from the earliest times, and have continued their efforts with varying degrees of success ever since.

The word rodeo was only occasionally used for American cowboy sports until the 1920s, and professional cowboys themselves did not officially adopt the term until 1945. Similarly, there was no attempt to standardize the events needed to make up such sporting contests until 1929. From the 1880s through the 1920s, frontier days, stampedes, and cowboy contests were the most popular names. Cheyenne Frontier Days, which began in 1897, remains the most significant annual community celebration even today. Until 1922, cowboys and cowgirls who won at Cheyenne were considered the world’s champions. Until 1912, organization of these community celebrations fell to local citizen committees who selected the events, made the rules, chose officials, arranged for the stock, and handled all other aspects of the festival. Many of these early contests bore more resemblance to Buffalo Bill's Wild West than to contemporary rodeo. While today's PRCA-sanctioned rodeos must include five events: calf roping, bareback and saddle bronc riding, bull riding, and steer wrestling, with the option to also hold steer roping and team roping, their Pre-World War I counterparts often offered only two of these contests. The day-long programs included diverse activities including Pony Express races, nightshirt races, and drunken rides. One even featured a football game. Almost all contests were billed as world's championships, causing confusion that endures to this day. Cowboys and cowgirls often did not know the exact events on offer until they arrived on site, and did not learn the rules of competition until they had paid their entry fees.

Before World War II, the most popular rodeo events included trick and fancy roping, trick and fancy riding, and racing. Trick and fancy roping contestants had to make figures and shapes with their lassos before releasing them to capture one or several persons or animals. These skills had to be exhibited on foot and on horseback. Fancy roping was the event most closely identified with the vaqueros, who invented it. In trick and fancy riding, athletes performed gymnastic feats on horseback while circling the arena at top speed. Athletes in these events were judged, much like those in contemporary gymnastics. The most popular races included Roman standing races wherein riders stood with one foot on the back of each of a pair of horses, and relays in which riders changed horses after each lap of the arena. Both were extremely dangerous, and sometimes fatal.

Another great difference between these colorful contests and their modern counterparts was that there were no chutes or gates, and no time limits. Rough stock were blindfolded and snubbed in the center of the arenas where the riders mounted. The animals were then set free. In the vast arenas, which usually included a racetrack, rides often lasted more than 10 minutes, and sometimes the contestants vanished from view of the audience.

During this era, women rode broncs and bulls and roped steers. They also competed in a variety of races, as well as trick and fancy roping and riding. In all of these contests, they often competed against men and won. Hispanics, blacks and Native Americans also participated in significant numbers. In some places, Native Americans were invited to set up camp on the grounds, perform dances and other activities for the audience, and participate in contests designated solely for them, Some rodeos did discriminate against one or more of these groups, but most were open to anyone who could pay the entry fee.

All this began to change in 1912, when a group of Calgary businessmen hired roper Guy Weadick to manage, promote, and produce his first Stampede. Weadick selected the events, determined rules and elegibility, chose the officials, and invited well-known cowboys and cowgirls to take part. He hoped to pit the best Canadian hands against those of the US and Mexico, but Mexican participation was severely limited by the civil unrest in that country. Nonetheless, the Stampede was a huge success, and Weadick followed with the Winnipeg Stampede of 1913, and much less successful New York Stampede of 1916.Although Weadick’s last production, the 1919 Calgary Stampede, was only a minor success, he led the way for a new era in which powerful producers, not local committees, would dominate rodeo and greatly expand its audience.

Rodeo enjoyed enormous popularity in New York, Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia, as well as in London, Europe, Cuba, South America, and the Far East in the 1920s and 1930s.Today, none of those venues is viable. Despite numerous tours abroad before World War II, rodeo is really significant only in North America. While it does exist in Australia and New Zealand, top athletes from those countries come to America to seek their fortunes. Some Latin American countries have contests called rodeos but these have none of the events found in the North American version.

Organizations governing rodeo

There are numerous organizations governing rodeo today, each with slightly different rules, different roles for women, and different events.

The oldest and largest sanctioning body of professional rodeo is the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) which sanctions around 700 rodeos annually. The Professional Bull Riders (PBR) is a more recent organization dedicated solely to the bull riding event. There are also high-school rodeos, sponsored by the National High School Rodeo Association, amateur rodeos, "Little Britches" rodeos for preteens and early adolescents, mostly governed by the American Junior Rodeo Association, and rodeos for women. Many colleges, particularly land grant colleges in the west, have rodeo teams. The National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association is responsible for the College National Rodeo Finals (CNFR) held each June in Casper, WY.

Until recently, the most important was PRCA. They crown the World Champions at the National Finals Rodeo (NFR), held since 1985 at Las Vegas, Nevada, it features the top fifteen money-winners in seven events. The athletes who have won the most money, including NFR earnings, in each event are the World’s Champions. However, since 1992, Professional Bull Riders, Inc. (PBR) has siphoned off the top athletes in that event, and holds its own multi- million dollar finals in Las Vegas prior to the NFR. Much of their success usually attributed to the leadership of nine-time world champion and hall of fame honoree Ty Murray. Women’s barrel racing is governed by the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA), and through 2006 held its finals along with the PRCA with the cowboys at the NFR.[15]

Contemporary rodeo is a lucrative business. More than 7,500 cowboys compete for over thirty million dollars at 650 rodeos annually. Women’s barrel racing, sanctioned by the WRPA, has taken place at most of these rodeos. Over 2,000 barrel racers compete for nearly four million dollars annually. What few people realize is that there are also professional cowgirls competing in bronc and bull riding, team roping and calf roping. Under the auspices of the PWRA, a WPRA subsidiary, these 120 women go largely unnoticed, with only twenty rodeos and seventy individual contests available annually. The total purse at their National Finals is only $50,000.[16] Meanwhile, the upstart PBR now boasts 700 members from three continents, and ten million dollars in prize money. [17]

Rodeo contests are classified as timed events, where athletes try to be the swiftest, and rough stock events, in which athletes attempt to stay atop a bucking animal for a designated time. The PRCA timed events are calf roping, steer roping, team roping, and steer wrestling. However, steer roping is not included in the NFR, while barrel racing is. In barrel racing, the rider with the fastest time completing a cloverleaf pattern around three barrels without toppling them is the winner. Bull riding, saddle bronc riding, and bareback bronc riding are the standard rough stock events. In PRCA rodeos, riders must stay on the animals for eight seconds. Different organizations have various time limits for different events.[18]

Other rodeo governing bodies include American Junior Rodeo Association (AJRA) for contestants under twenty years of age; Canadian Professional Rodeo Association (CPRA); National High School Rodeo Association (NHSRA); National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association (NIRA); National Little Britches Rodeo Association (NLBRA), ages eight to eighteen; Senior Pro Rodeo (SPR), for athletes forty years old or over. Each one has its own regulations and its own method of determining champions. Every organization requires its athletes to have membership cards or permits in order to compete in its events. Athletes must participate only in rodeos sanctioned by their own governing body or one that has a mutual agreement with theirs. Rodeo committees must pay sanctioning fees to the appropriate governing bodies, and employ the needed stock contractors, judges, announcers, bull fighters, and barrel men from their approved lists.

So many organizations and detailed rules came late to rodeo. Until the mid-1930’s, every rodeo was independent, and selected its own events from among nearly one hundred different contests. Until World War I, there was little difference between rodeo and “Charreada”, and athletes from the US, Mexico and Canada competed freely in all three countries. Subsequently, “Charreada” was formalized as an amateur team sport and the international competitions ceased, although “Charreada” remains a popular amateur sport in Mexico and the Hispanic communities of the U.S. today.

While the concept of a Rodeo often conjures up Hollywood movie images of dusty cowboys in rural arenas, the modern professional rodeo is a very different sport. Its long season peaks on the July 4th weekend, but concludes with the world’s richest rodeo, the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) Wrangler National Finals Rodeo (NFR) in Las Vegas, Nevada in December.

The term rodeo was first used in English approximately 1834 to refer to a cattle round-up. it is derived from the Spanish word rodear, meaning to surround or go around, used to refer to "a pen for cattle at a fair or market," derived from the Latin rota or rotare, meaning to rotate or go around.

Events

Timed events

* Barrel racing and pole bending - the timed speed and agility events seen in rodeo as well as gymkhana or O-Mok-See competition. Both men and women compete in speed events at gymkhanas or O-Mok-Sees; however, at rodeos, barrel racing is an exclusively women's sport. In a barrel race, horse and rider gallop around a cloverleaf pattern of barrels, making agile turns without knocking the barrels over. In pole bending, horse and rider run the length of a line of six upright poles, turn sharply and weave through the poles, turn again and weave back, then return to the start.

* Steer wrestling - Also known as "Bulldogging," this is a rodeo event where the rider jumps off his horse onto a steer and 'wrestles' it to the ground by grabbing it by the horns. This is probably the single most physically dangerous event in rodeo for the cowboy, who runs a high risk of jumping off a running horse head first and missing the steer, or of having the thrown steer land on top of him, sometimes horns first.

* Goat tying - usually an event for women or pre-teen girls and boys, a goat is staked out while a mounted rider runs to the goat, dismounts, grabs the goat, throws it to the ground and ties it in the same manner as a calf. This event was designed to teach smaller or younger riders the basics of calf roping without the more complex need to also lasso the animal.

Roping

Roping encompasses a number of timed events that are based on the real-life tasks of a working cowboy, who often had to capture calves and adult cattle for branding, medical treatment and other purposes. A lasso or lariat is thrown over the head of a calf or the horns and heels of adult cattle, and the animal is secured in a fashion dictated by its size and age.

* Calf Roping, sometimes called Tie-down roping - A calf is roped around the neck by a lariat, the horse stops and sets back on the rope while the cowboy dismounts, runs to the calf, throws it to the ground and ties three feet together. (If the horse throws the calf, the cowboy must lose time waiting for the calf to get back to its feet so that the cowboy can do the work. The job of the horse is to hold the calf steady on the rope) This activity is still practiced on modern working ranches for branding, medical treatment, and so on.

* Team roping, also called "heading and heeling," is the only rodeo event where men and women riders may compete together. Two people capture and restrain a full-grown steer. One horse and rider, the "header," lassos a running steer's horns, while the other horse and rider, the "heeler," lassos the steer's two hind legs. Once the animal is captured, the riders face each other and lightly pull the steer between them, so that it loses its balance, thus in the real world allowing restraint for treatment.

* Breakaway roping - an easier form of calf roping where a very short lariat is used, tied lightly to the saddle horn with string and a flag. When the calf is roped, the horse stops, allowing the calf to run on, flagging the end of time when the string and flag breaks from the saddle. In the United States, this event is primarily for women of all ages and boys under 12, while in some nations where traditional calf roping is frowned upon, riders of both genders compete.

"Rough Stock" competition

In spite of popular myth, most modern "broncs" are not in fact wild horses, but are more commonly spoiled riding horses or horses bred specifically as bucking stock.

* Bronc riding - there are two divisions in rodeo, bareback bronc riding, where the rider is only allowed to hang onto a bucking horse with a surcingle, and saddle bronc riding, where the rider is allowed a specialized western saddle without a horn (for safety) and may hand onto a heavy lead rope attached to a halter on the horse.

* Bull Riding - an event where the cowboys ride full-grown bulls instead of horses, skills similar to bareback bronc riding are required. Rodeo clowns, now known as Bullfighters, word during bull riding competition to help prevent injury to fallen riders.

Early history of rodeo

Rodeo stresses its western folk hero image and its being a genuinely American creation. But in fact it grew out of the practices of Spanish ranchers and their Mexican ranch hands (vaqueros), a mixture of cattle wrangling and bull fighting that dates back to the sixteenth-century conquistadors.

One of the activities introduced by the Spanish and incorporated into rodeo was bull riding. Another was steer wrestling, involved wrestling the steer to the ground by riding up behind it, grabbing its tail, and twisting it to the ground. Bull wrestling had been part of an ancient tradition throughout the ancient Mediterranean world including Spain. The ancient Minoans of Crete practiced bull jumping, bull riding, and bull wrestling. Bull wrestling may have been one of the Olympic sports events of the ancient Greeks.

The events spread throughout the Kingdom of New Spain and was found at fairgrounds, racetracks, fiestas, and festivals in nineteenth century southwestern areas that now comprise the United States. However, unlike the roping, riding, and racing, this contest never attracted a following among Anglo cowboys or audiences. It is however a favorite event included in the charreada, the style of rodeo which originated in the Mexican state of Jalisco.

There would probably be no steer wrestling at all in American rodeo were it not for a black cowboy from Texas named Bill Pickett who devised his own unique method of bulldogging steers. He jumped from his horse to a steer’s back, bit its upper lip, and threw it to the ground by grabbing its horns. He performed at local central Texas fairs and rodeos and was discovered by an agent, who signed him on a tour of the West with his brothers. He received sensational national publicity with his bulldogging exhibition at the 1904 Cheyenne Frontier Days. This brought him a contract with the famous 101 Ranch Wild West, where he spent many years performing in the United States and abroad.

Pickett attracted many imitators who appeared at rodeos and Wild West shows, and soon there were enough practitioners for promoters to stage contests. The first woman bulldogger appeared in 1913, when the great champion trick and bronc rider and racer Tillie Baldwin exhibited the feat. However, women's bulldogging contests never materialized. But cowboys did take up the sport with enthusiasm but without the lip-biting, and when rodeo rules were codified, steer wrestling was among the standard contests. Two halls of fame recognize Bill Pickett as the sole inventor of bulldogging, the only rodeo event which can be attributed to a single individual.

Rodeo itself evolved after the Texas Revolution and the US-Mexican War when Anglo cowboys learned the skills, attire, vocabulary, and sports of the vaqueros. Ranch-versus-ranch contests gradually sprang up, as bronc riding, bull riding, and roping contests appeared at race tracks, fairgrounds, and festivals of all kinds. William F. Cody (Buffalo Bill) created the first major rodeo and the first Wild West show in North Platte, Nebraska in 1882. Following this successful endeavor, Cody organized his touring Wild West show, leaving other entrepreneurs to create what became professional rodeo. Rodeos and Wild West shows enjoyed a parallel existence, employing many of the same stars, while capitalizing on the continuing allure of the mythic West. Women joined the Wild West and contest rodeo circuits in the 1890s and their participation grew as the activities spread geographically. Animal welfare groups began targeting rodeo from the earliest times, and have continued their efforts with varying degrees of success ever since.

The word rodeo was only occasionally used for American cowboy sports until the 1920s, and professional cowboys themselves did not officially adopt the term until 1945. Similarly, there was no attempt to standardize the events needed to make up such sporting contests until 1929. From the 1880s through the 1920s, frontier days, stampedes, and cowboy contests were the most popular names. Cheyenne Frontier Days, which began in 1897, remains the most significant annual community celebration even today. Until 1922, cowboys and cowgirls who won at Cheyenne were considered the world’s champions. Until 1912, organization of these community celebrations fell to local citizen committees who selected the events, made the rules, chose officials, arranged for the stock, and handled all other aspects of the festival. Many of these early contests bore more resemblance to Buffalo Bill's Wild West than to contemporary rodeo. While today's PRCA-sanctioned rodeos must include five events: calf roping, bareback and saddle bronc riding, bull riding, and steer wrestling, with the option to also hold steer roping and team roping, their Pre-World War I counterparts often offered only two of these contests. The day-long programs included diverse activities including Pony Express races, nightshirt races, and drunken rides. One even featured a football game. Almost all contests were billed as world's championships, causing confusion that endures to this day. Cowboys and cowgirls often did not know the exact events on offer until they arrived on site, and did not learn the rules of competition until they had paid their entry fees.

Before World War II, the most popular rodeo events included trick and fancy roping, trick and fancy riding, and racing. Trick and fancy roping contestants had to make figures and shapes with their lassos before releasing them to capture one or several persons or animals. These skills had to be exhibited on foot and on horseback. Fancy roping was the event most closely identified with the vaqueros, who invented it. In trick and fancy riding, athletes performed gymnastic feats on horseback while circling the arena at top speed. Athletes in these events were judged, much like those in contemporary gymnastics. The most popular races included Roman standing races wherein riders stood with one foot on the back of each of a pair of horses, and relays in which riders changed horses after each lap of the arena. Both were extremely dangerous, and sometimes fatal.

Another great difference between these colorful contests and their modern counterparts was that there were no chutes or gates, and no time limits. Rough stock were blindfolded and snubbed in the center of the arenas where the riders mounted. The animals were then set free. In the vast arenas, which usually included a racetrack, rides often lasted more than 10 minutes, and sometimes the contestants vanished from view of the audience.

During this era, women rode broncs and bulls and roped steers. They also competed in a variety of races, as well as trick and fancy roping and riding. In all of these contests, they often competed against men and won. Hispanics, blacks and Native Americans also participated in significant numbers. In some places, Native Americans were invited to set up camp on the grounds, perform dances and other activities for the audience, and participate in contests designated solely for them, Some rodeos did discriminate against one or more of these groups, but most were open to anyone who could pay the entry fee.

All this began to change in 1912, when a group of Calgary businessmen hired roper Guy Weadick to manage, promote, and produce his first Stampede. Weadick selected the events, determined rules and elegibility, chose the officials, and invited well-known cowboys and cowgirls to take part. He hoped to pit the best Canadian hands against those of the US and Mexico, but Mexican participation was severely limited by the civil unrest in that country. Nonetheless, the Stampede was a huge success, and Weadick followed with the Winnipeg Stampede of 1913, and much less successful New York Stampede of 1916.Although Weadick’s last production, the 1919 Calgary Stampede, was only a minor success, he led the way for a new era in which powerful producers, not local committees, would dominate rodeo and greatly expand its audience.

Rodeo enjoyed enormous popularity in New York, Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia, as well as in London, Europe, Cuba, South America, and the Far East in the 1920s and 1930s.Today, none of those venues is viable. Despite numerous tours abroad before World War II, rodeo is really significant only in North America. While it does exist in Australia and New Zealand, top athletes from those countries come to America to seek their fortunes. Some Latin American countries have contests called rodeos but these have none of the events found in the North American version.

Organizations governing rodeo

There are numerous organizations governing rodeo today, each with slightly different rules, different roles for women, and different events.

The oldest and largest sanctioning body of professional rodeo is the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (PRCA) which sanctions around 700 rodeos annually. The Professional Bull Riders (PBR) is a more recent organization dedicated solely to the bull riding event. There are also high-school rodeos, sponsored by the National High School Rodeo Association, amateur rodeos, "Little Britches" rodeos for preteens and early adolescents, mostly governed by the American Junior Rodeo Association, and rodeos for women. Many colleges, particularly land grant colleges in the west, have rodeo teams. The National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association is responsible for the College National Rodeo Finals (CNFR) held each June in Casper, WY.

Until recently, the most important was PRCA. They crown the World Champions at the National Finals Rodeo (NFR), held since 1985 at Las Vegas, Nevada, it features the top fifteen money-winners in seven events. The athletes who have won the most money, including NFR earnings, in each event are the World’s Champions. However, since 1992, Professional Bull Riders, Inc. (PBR) has siphoned off the top athletes in that event, and holds its own multi- million dollar finals in Las Vegas prior to the NFR. Much of their success usually attributed to the leadership of nine-time world champion and hall of fame honoree Ty Murray. Women’s barrel racing is governed by the Women’s Professional Rodeo Association (WPRA), and through 2006 held its finals along with the PRCA with the cowboys at the NFR.[15]

Contemporary rodeo is a lucrative business. More than 7,500 cowboys compete for over thirty million dollars at 650 rodeos annually. Women’s barrel racing, sanctioned by the WRPA, has taken place at most of these rodeos. Over 2,000 barrel racers compete for nearly four million dollars annually. What few people realize is that there are also professional cowgirls competing in bronc and bull riding, team roping and calf roping. Under the auspices of the PWRA, a WPRA subsidiary, these 120 women go largely unnoticed, with only twenty rodeos and seventy individual contests available annually. The total purse at their National Finals is only $50,000.[16] Meanwhile, the upstart PBR now boasts 700 members from three continents, and ten million dollars in prize money. [17]

Rodeo contests are classified as timed events, where athletes try to be the swiftest, and rough stock events, in which athletes attempt to stay atop a bucking animal for a designated time. The PRCA timed events are calf roping, steer roping, team roping, and steer wrestling. However, steer roping is not included in the NFR, while barrel racing is. In barrel racing, the rider with the fastest time completing a cloverleaf pattern around three barrels without toppling them is the winner. Bull riding, saddle bronc riding, and bareback bronc riding are the standard rough stock events. In PRCA rodeos, riders must stay on the animals for eight seconds. Different organizations have various time limits for different events.[18]

Other rodeo governing bodies include American Junior Rodeo Association (AJRA) for contestants under twenty years of age; Canadian Professional Rodeo Association (CPRA); National High School Rodeo Association (NHSRA); National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association (NIRA); National Little Britches Rodeo Association (NLBRA), ages eight to eighteen; Senior Pro Rodeo (SPR), for athletes forty years old or over. Each one has its own regulations and its own method of determining champions. Every organization requires its athletes to have membership cards or permits in order to compete in its events. Athletes must participate only in rodeos sanctioned by their own governing body or one that has a mutual agreement with theirs. Rodeo committees must pay sanctioning fees to the appropriate governing bodies, and employ the needed stock contractors, judges, announcers, bull fighters, and barrel men from their approved lists.

So many organizations and detailed rules came late to rodeo. Until the mid-1930’s, every rodeo was independent, and selected its own events from among nearly one hundred different contests. Until World War I, there was little difference between rodeo and “Charreada”, and athletes from the US, Mexico and Canada competed freely in all three countries. Subsequently, “Charreada” was formalized as an amateur team sport and the international competitions ceased, although “Charreada” remains a popular amateur sport in Mexico and the Hispanic communities of the U.S. today.