♘امیرحسین♞

♘ مدیریت انجمن اسب ایران ♞

The Tekke or Tekke Turkoman (or Teke Turkoman) is bred today by Akhal-Tekke and Tekke tribesmen living in Iran, Afghanistan and, possibly, in India. The Tekke is the long-distance runner on the flat, the horse who is referred to in the Abbas Pasha Manuscript as "The Greyhound of the North."

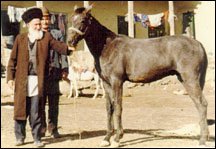

Many Tekke tribesmen (and many other Turkmen) fled to these countries after the battle of Geok Tepe in the 1880s. Another large group fled the USSR after Red October, and another group fled when Stalin made it illegal throughout the USSR for any one to own a horse of their own. Among those who fled "Russia" (as these tribesmen continue to call any part of the fUSSR) is a true "Ak Sakal" (a white beard, thus a wise one) of the Tekke horse, Mr. Yazdani, who fled Turkmenistan with his father in the 1920s with his father and their horses. He now breeds Tekkes in northern Iran. He is shown here with a six month old colt he is currently raising.

The Tekke Turkmen living in Iran do not call their horses "Akhal-Teke" even if they are from that tribe. Some other names are, however used. Wealthy families who fled Turkmenistan sometimes set up breeding operations of their own in Iran or Afghanistan, and the horses became known by the name of the breeder. Sometimes the horses take on the names of the area in which they were bred. Thus, one finds the "Yatimcheh" horses, who are all a variation of bay; and the Jargalan, which orignates from the Jargalan area of Iran. Other studs one may find reference to from time to time is called "Tuch-Mohamad-Khodeh" in the southwest of Jargalan, and the Ghara Tepe Sheik stud of Mrs. Louise Firouz.

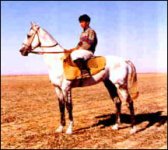

The Tekke type is characterized by angularity, although it is often not quite as extreme as that seen in the Akhal-Teke. The Tekke is a narrow horse who may be maneless, or may appear as if someone had pasted a huge false eyelash down its crest. The forelock is often entirely absent. The tail, on the other hand, when well cared for, can be quite thick and luxurious. The head has a straight profile, often with what Linda Tellington-Jones describes as a "quirk-bump" between or below the eyes. Eyes are large, almond-shaped and often hooded. The muzzle is square and the nostrils quite large. The head is held high, at an angle to the neck, and the neck itself is set high on powerful and sloping shoulders. The back is long but not overly so, with the coupling (area between the false ribs and the hips) well muscled, powerful and flexible. The angle from the point of the hip to the point of the buttock is not quite so steep as it is in the Yamoud, nor is the tail set on quite so low. The croup slopes gently. The limbs are long, and "dry," with every muscle and tendon clearly defined, and the pastern of both the fore and hind limbs long. There may appear to be less "depth to the girth" than there is in the Yamoud or the English Thoroughbred, but this is often simply an illusion caused by the extreme length of the legs. The Tekke is a horse with "a lot of daylight under him," and everything about his posture and refinement speaks of royalty.

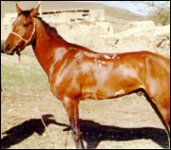

a rare Yatimcheh Tekke

The Tekke comes in all the colors of the Turanian horse, including roan. Some substrains are characterized by particular colors; the Yatimcheh Tekke at left, one of a very rare substrain, is always some shade of bay.

During the reign of the Shah, the Turkmen and the Royal Horse Society bred the Tekke horses they had brought with them from Turkmenistan, and the Yamoud and Goklan horses who had lived there all along, for their own pride and for racing. For a very short time, the Royal Horse Society attempted a registry for these horses. Occasionally, Akhal-Tekes from the Komsomol stud in Ashkabad were brought in (though their names were changed to Persian ones when they entered Iran). The Royal Horse Society also brought in English Thoroughbreds to cross with Turkomans to increase their speed at the short distances preferred by high-society and international patrons of the RHS's racetrack in Tehran.

Some Turkmen bred the partbreds for the large prizes awarded by the track -- as part of the incentive to crossbreed, purebred Turkmen horses were not allowed to compete. Other Turkmen complained that the partbreds were "too uneconomical to keep," that they did not fare well on the steppe and ate too much, and continued to breed their own horses, and race them on their own makeshift tracks on the steppe.

In 1979, Iran underwent a revolution. Afterward, a decree was handed down saying that forbade anyone to own more than one horse. Turkmen and other private breeders either hid their horses away, or, far more often, brought them to water holes and the steppe and simply let them go.

Millennia of being bred in taboons in the wild paid off for these horses. The mares gathered into bands and were able to withstand at first irate wheat farmers who drove them further onto the steppe, and the wolves who gave the area its ancient name, Hyrcania.

In the late 1980s, the decree was reversed. Private breeders and Turkmen alike returned to the steppes, where their mares now ran wild. They were able to capture a few, and blood testing later revealed that these mares, and their wild-born offspring (some stallions were also released) were purebred Turkomans.

The Ghara Tepe Sheik stud, owned by Mrs. Firouz, was able to collect five Tekke and one Goklan mare, and acquired the breeding stallion Duldul. The Akhal-Teke stallion Ervint (known as Terigat when he lived at Komsomol) was also available through the Horse Society. Slowly the Tekke and Yamoud populations grew, and informal races are held once again in the Jargalan district.

The information on this page comes from Mrs. Louise Firouz and Farshad Maloufi, DVM, and their friends in the Turkmen community in Iran. The photographs were taken by and are © 1998 Farshad Maloufi and Louise L Firouz are used here with their permission.

Many Tekke tribesmen (and many other Turkmen) fled to these countries after the battle of Geok Tepe in the 1880s. Another large group fled the USSR after Red October, and another group fled when Stalin made it illegal throughout the USSR for any one to own a horse of their own. Among those who fled "Russia" (as these tribesmen continue to call any part of the fUSSR) is a true "Ak Sakal" (a white beard, thus a wise one) of the Tekke horse, Mr. Yazdani, who fled Turkmenistan with his father in the 1920s with his father and their horses. He now breeds Tekkes in northern Iran. He is shown here with a six month old colt he is currently raising.

The Tekke Turkmen living in Iran do not call their horses "Akhal-Teke" even if they are from that tribe. Some other names are, however used. Wealthy families who fled Turkmenistan sometimes set up breeding operations of their own in Iran or Afghanistan, and the horses became known by the name of the breeder. Sometimes the horses take on the names of the area in which they were bred. Thus, one finds the "Yatimcheh" horses, who are all a variation of bay; and the Jargalan, which orignates from the Jargalan area of Iran. Other studs one may find reference to from time to time is called "Tuch-Mohamad-Khodeh" in the southwest of Jargalan, and the Ghara Tepe Sheik stud of Mrs. Louise Firouz.

The Tekke type is characterized by angularity, although it is often not quite as extreme as that seen in the Akhal-Teke. The Tekke is a narrow horse who may be maneless, or may appear as if someone had pasted a huge false eyelash down its crest. The forelock is often entirely absent. The tail, on the other hand, when well cared for, can be quite thick and luxurious. The head has a straight profile, often with what Linda Tellington-Jones describes as a "quirk-bump" between or below the eyes. Eyes are large, almond-shaped and often hooded. The muzzle is square and the nostrils quite large. The head is held high, at an angle to the neck, and the neck itself is set high on powerful and sloping shoulders. The back is long but not overly so, with the coupling (area between the false ribs and the hips) well muscled, powerful and flexible. The angle from the point of the hip to the point of the buttock is not quite so steep as it is in the Yamoud, nor is the tail set on quite so low. The croup slopes gently. The limbs are long, and "dry," with every muscle and tendon clearly defined, and the pastern of both the fore and hind limbs long. There may appear to be less "depth to the girth" than there is in the Yamoud or the English Thoroughbred, but this is often simply an illusion caused by the extreme length of the legs. The Tekke is a horse with "a lot of daylight under him," and everything about his posture and refinement speaks of royalty.

a rare Yatimcheh Tekke

The Tekke comes in all the colors of the Turanian horse, including roan. Some substrains are characterized by particular colors; the Yatimcheh Tekke at left, one of a very rare substrain, is always some shade of bay.

During the reign of the Shah, the Turkmen and the Royal Horse Society bred the Tekke horses they had brought with them from Turkmenistan, and the Yamoud and Goklan horses who had lived there all along, for their own pride and for racing. For a very short time, the Royal Horse Society attempted a registry for these horses. Occasionally, Akhal-Tekes from the Komsomol stud in Ashkabad were brought in (though their names were changed to Persian ones when they entered Iran). The Royal Horse Society also brought in English Thoroughbreds to cross with Turkomans to increase their speed at the short distances preferred by high-society and international patrons of the RHS's racetrack in Tehran.

Some Turkmen bred the partbreds for the large prizes awarded by the track -- as part of the incentive to crossbreed, purebred Turkmen horses were not allowed to compete. Other Turkmen complained that the partbreds were "too uneconomical to keep," that they did not fare well on the steppe and ate too much, and continued to breed their own horses, and race them on their own makeshift tracks on the steppe.

In 1979, Iran underwent a revolution. Afterward, a decree was handed down saying that forbade anyone to own more than one horse. Turkmen and other private breeders either hid their horses away, or, far more often, brought them to water holes and the steppe and simply let them go.

Millennia of being bred in taboons in the wild paid off for these horses. The mares gathered into bands and were able to withstand at first irate wheat farmers who drove them further onto the steppe, and the wolves who gave the area its ancient name, Hyrcania.

In the late 1980s, the decree was reversed. Private breeders and Turkmen alike returned to the steppes, where their mares now ran wild. They were able to capture a few, and blood testing later revealed that these mares, and their wild-born offspring (some stallions were also released) were purebred Turkomans.

The Ghara Tepe Sheik stud, owned by Mrs. Firouz, was able to collect five Tekke and one Goklan mare, and acquired the breeding stallion Duldul. The Akhal-Teke stallion Ervint (known as Terigat when he lived at Komsomol) was also available through the Horse Society. Slowly the Tekke and Yamoud populations grew, and informal races are held once again in the Jargalan district.

The information on this page comes from Mrs. Louise Firouz and Farshad Maloufi, DVM, and their friends in the Turkmen community in Iran. The photographs were taken by and are © 1998 Farshad Maloufi and Louise L Firouz are used here with their permission.