♘امیرحسین♞

♘ مدیریت انجمن اسب ایران ♞

The Turkoman horse, or Turkmene, was an ancient breed from Turkmenistan, now extinct. Modern representatives include the Akhal-Teke and the Yamud. Horses bred in the area are still referred to as Turkoman, and have similar characteristics. They have been influential in many breeds, including the Thoroughbred.

The Turkoman horse has an extremely slender body, similar to a greyhound. Although they may look weak, the breed is actually one of the toughest in the world. They have a straight profile, long neck, and sloping shoulders. Their back is long, with sloping quarters and a tucked up abdomen. They have long and muscular legs.

The coat of a Turkomen horse can be of any color, and usually possesses a metallic glow to it. The horses range from 15-16 hh.

The horses are raised in an unusual manner, with the mares kept in semi-wild herds that have to fend for themselves against the weather and predators, finding their own food. Colts are caught at six months, when their training begins. The colts are kept on long tethers, usually for life. At only eight months of age, they are saddled and ridden by young and lightweight riders, racing on the track by the time they are one. The horses are bred for racing, and are quite talented.

The Turkomen horses are fed a special high-protein diet of broiled chicken, barley, dates, raisins, alfalfa, and mutton fat. They wear thick felt blankets to cause sweating on hot days, keeping them lean and free from body fat.

The horses have incredible stamina. They have free-flowing movement and a good temperament.

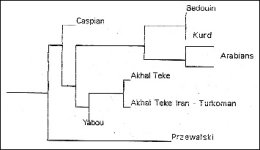

The Turkoman and the Arabian compared

Perhaps this is a good time and place to consider the differences which existed at that time between the horse we know as having been recognizably "Arabian" and that we know as being recognizably "Turkoman/Turanian" and understand how the two came to be confused.

The Turkoman and the Arabian horse, in their purest old forms, were very like one another in some ways and very different in others. Both had excellent speed and stamina. Both had extremely fine coats and delicate skin, unlike that of any breed found in Europe. They both had large eyes, wide foreheads and tapering muzzles. They both came from very arid environments. Here, however, the similarities between the Turkoman of Central Asia and the Nejdi Arabian end, and the horses begin to diverge to suit their environments and the fighting styles of their breeders.

Among the differences which are probably due, in the main, to environmental influences are these:

The Turkoman as small hooves, and the old Nedji Arabian fairly large hooves for its size. This was an adaptation to footing. The steppes of Central Asia consisted of hard, rocky ground, covered somewhat with coarse sand somewhat more like fine gravel and clumps of stiff, parched vegetation. A smaller hoof was needed here to be able to negotiate the embedded rocks and clumps without become stuck in them. In the Central Arabian desert, there is deep sand. Large rocks are often not embedded and can be moved by a passing hoof. The larger hoof is needed here to cope with this type of terrain.

The spine of the Turkoman, the Tekke Turkoman (and today in many cases the Akhal-Teke) in particular, is much longer than that of the Arabian. The reason for this may likely be that when riding long distances, the Turkoman was expected to trot, and the Arabian was not. Indeed, a fluid trot may not have come naturally to the old Arabian at all, as trotting on any horse over heavy sand is extremely tiring and difficult. In general, one will notice that the more difficult the "going" underfoot, the shorter-backed a "native" type of horse will be (and some such horses will also show a tendency to substitute the pace or a single-foot gait for the trot, to avoid the forging and striking that too short a back on too long-legged a horse tends to produce).

The Turkoman is on the whole taller than the desert-bred Arabian. This, again, may have to do with the comparative stability of footing which the Turkoman often enjoyed. Height would put Arabians in the desert at a disadvantage, as the higher one's center of gravity is over footing of any kind, the more energy is required to maintain it in balance; insecure, shifting footing takes more energy still. A taller horse under the same circumstances is likely to tire sooner than a shorter one.

In other words, the Turkoman is ideally suited for noticing, outrunning and outlasting predators, and moving to and from water, on the Central Asian Steppes; and the Arabian is ideally suited for noticing, outrunning and outlasting predators, and moving to and from water, in the Central Arabian Desert.

Among the differences which are probably due, in the main, to suitability for use and thus selective breeding, are these:

The Turkoman is often nearly mane-less. Considering that it was originally used as a "moving platform" for mounted archers, this should not be all that surprising. A flowing mane would greatly interfere with the drawing of a bow. Certainly one could braid a mane in preparation for a fight, but of course in this case one would have to know in advance that the fight was coming, which wasn't always the case. The Arabs, when they fought on horseback, used a very long lance or a short sword, with which a long mane was less likely to interfere or become entangled.

The Arabian carries its tail high when galloping, and higher than most when walking or trotting. The Turkoman runs with its tail streaming behind it, where it does not interfere with the drawing of the bow when taking the famous Parthian Shot.

In other words, the Turkoman is the ideal platform for mounted archers who shot on the run, and the Arabian is the perfect platform for lancers and swordsmen.

Among the differences which may be due, in the main, to both environmental and breeding influences -- or whose influence is unknown -- are these:

The Turkoman horse, in all its form, has a coat which glows with a metallic sheen. Not all horses in a population will show it, and some glow more than others, but as a whole, a glowing coat is a hallmark of the breed. This is due to a change in the structure of the individual hair. Many theories have been put forth as to why the Turkoman glows, but none explain why the Turkoman horses in particular benefit from this genetic difference and why other horses would not.

The Turkoman horse is narrower in the body than the Arabian, or indeed than any other breed of horse. This helps it to dissipate heat quickly, but it is also a great aid in twisting and turning in the saddle, which would be invaluable to mounted archers who need to shoot in any direction, as opposed to lancers who need a firm footing from which to thrust a lance. Lance-throwing from horseback would be far easier on an Arabian -- whose "wider wheel base" would also help with making the sharp turns that close-in fighting requires.

In other words, the Turkoman was the ideal horse for the Turkmen, and the Arab was the ideal horse for the Arabs.

So how did this confusion over which horse was which arise? There were probably several contributing factors.

One of them was that when the first Oriental horses were imported to England, it simply didn't matter what kind of horse it was, so long as it was elegant and fast and could race.

Another comes from Islam. Throughout the Islamic world in previous times, it was commonplace for Arabs to "adopt converts into the tribe," so to speak, especially if they were wealthy and/or in positions of power. A Turk who converted to Islam was taught Arabic (to read the Koran in Arabic) and called an "Arab" by the Arabs. The Turks, being nomads, were generally open to new ideas from all over the place; many who were previously Buddhist or Zoroastrians embraced Islam and thus became nominally "Arabs." Thus their horses might have gotten that appellation by association. (For more information on this process, see Frye below).

All this may have contributed to the fact that in England, as Sidney tells us, "Every Oriental horse -- Turk, Barb or Egyptian bred -- is called an Arab in this country."

How much the Arabian and the Turkoman have been crossed in the past is open to debate. There are those who believe that this was never done, on either side; and it may well be that in remote places like the Nejd the core Arabian was kept "pure," just as the Turkoman would have been kept "pure" by the most nomadic tribes of Turkmen.

However, it is very likely that there was some -- and in some cases a good deal of -- intermingling between these two types of Oriental hotblood, especially where their borders met. We know that Turkoman stallions were kept for use by the elite palace guards of the Caliph of Baghdad, and that it was these stallions which he used for breeding with his Arabian mares. It was probably from these horses that the Muniqui Arabian arose.

"Turks" and the English Thoroughbred

The idea that the Turkoman horse, in any of its many types and strains, may have influenced the English Thoroughbred in any way is anathema to many people. But this is not only possible, but very probable.

It has been argued--mainly by Arabian proponent Lady Wentworth--that all the "Turks" listed in Weatherby's General Stud Book are actually "Arabians of the highest class" who are only called Turks because they were bought or taken as prizes of war in Turkey and the Crimea. There is, however, plenty of evidence that the Turks were actually Turks (Turkomans) and not mislabelled Arabians.

The first Turkoman recorded in England is said by Marvin to have been a stallion brought over by Colonel Valentine Baker, who wished to see it used to breed with the English Thoroughbred. We have not yet come across any information as to what happened to that horse once he reached England.

Turkomans were brought to England by soldiers stationed in various parts of the East, the most famous of which was the stallion Merv, who was brought to England by Baker Pacha in the 19th century. What was so astonishing about Merv at the time was the incredibly high stud fee which was charged for his services, £85, which at that time was considered exorbitant for any stallion. Unfortunately, other Englishmen did not esteem Merv the way Baker Pacha did. Sidney quotes a correspondent who had seen Merv as saying, "He looked to me about 16 hands high, fine shoulders, good head and neck, fine skin, good wearing legs, bad feet and leggy. I thought him unsuited to breed hunters ... he looked to me about an 11 stone horse, and not like going through dirt." [A stone = 14 lb, so an 11 stone horse would be one expected to be able to carry about 150 pounds or about 68 kg.] Merv covered no mares in England, and in 1877 he was sold to the Earl of Claremont's stud in Ireland.

Turks on the Continent

Turkoman horses, aside from being occasional gifts of state, were often brought into Western Europe by various individuals, most connected with the military in some way. Some of these horses have had a profound impact on various European warmblood breeds.

During the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, one of the most universally acclaimed war and racing horses in Europe was the Neapolitan Courser. Gervaise Markham, Master of Horse to James I of England, describes the Neapolitan in terms which will sound very familiar to the fancier of the Turanian horse:

"A horse of a strong and comely fashion, loving disposition, and infinite courageousness. His limbs and general features are so strong and well-knit together that he has ever been reputed the only beast for the wars, being naturally free from fear or cowardice. His head is long, lean and very slender; and does from eye to nose bend like a hawk's beak. He has a great, full eye, a sharp ear, and a straight leg, which, to an over curious eye might appear too slender -- which is all the fault curiosity itself and find. They are naturally of a lofty pace, loving to their rider, most strong in their exercise, and to conclude, as good in all points that no foreign race has ever borne a tithe so much excellence."

Markham preferred the English Thoroughbred first among all breeds of horses; the Neapolitan second, and the steppe-bred Turk third, notice that he had seen Turks racing on English race courses. (This would have been around 1566-1625.) He also noted of the Turks he had seen that, "Naturally they desire to amble, and, which is most strange, their trot is full of pride and gracefulness."

The most well-known of these horses is possibly Turkmein Atti, (one of many spellings of this horse's name). Although a drawing of him done (presumably) from life shows a horse with many Arabian characteristics, the name is curious in that it means "Turkmen horse" in Turkmenian.

The Turkoman horse has an extremely slender body, similar to a greyhound. Although they may look weak, the breed is actually one of the toughest in the world. They have a straight profile, long neck, and sloping shoulders. Their back is long, with sloping quarters and a tucked up abdomen. They have long and muscular legs.

The coat of a Turkomen horse can be of any color, and usually possesses a metallic glow to it. The horses range from 15-16 hh.

The horses are raised in an unusual manner, with the mares kept in semi-wild herds that have to fend for themselves against the weather and predators, finding their own food. Colts are caught at six months, when their training begins. The colts are kept on long tethers, usually for life. At only eight months of age, they are saddled and ridden by young and lightweight riders, racing on the track by the time they are one. The horses are bred for racing, and are quite talented.

The Turkomen horses are fed a special high-protein diet of broiled chicken, barley, dates, raisins, alfalfa, and mutton fat. They wear thick felt blankets to cause sweating on hot days, keeping them lean and free from body fat.

The horses have incredible stamina. They have free-flowing movement and a good temperament.

The Turkoman and the Arabian compared

Perhaps this is a good time and place to consider the differences which existed at that time between the horse we know as having been recognizably "Arabian" and that we know as being recognizably "Turkoman/Turanian" and understand how the two came to be confused.

The Turkoman and the Arabian horse, in their purest old forms, were very like one another in some ways and very different in others. Both had excellent speed and stamina. Both had extremely fine coats and delicate skin, unlike that of any breed found in Europe. They both had large eyes, wide foreheads and tapering muzzles. They both came from very arid environments. Here, however, the similarities between the Turkoman of Central Asia and the Nejdi Arabian end, and the horses begin to diverge to suit their environments and the fighting styles of their breeders.

Among the differences which are probably due, in the main, to environmental influences are these:

The Turkoman as small hooves, and the old Nedji Arabian fairly large hooves for its size. This was an adaptation to footing. The steppes of Central Asia consisted of hard, rocky ground, covered somewhat with coarse sand somewhat more like fine gravel and clumps of stiff, parched vegetation. A smaller hoof was needed here to be able to negotiate the embedded rocks and clumps without become stuck in them. In the Central Arabian desert, there is deep sand. Large rocks are often not embedded and can be moved by a passing hoof. The larger hoof is needed here to cope with this type of terrain.

The spine of the Turkoman, the Tekke Turkoman (and today in many cases the Akhal-Teke) in particular, is much longer than that of the Arabian. The reason for this may likely be that when riding long distances, the Turkoman was expected to trot, and the Arabian was not. Indeed, a fluid trot may not have come naturally to the old Arabian at all, as trotting on any horse over heavy sand is extremely tiring and difficult. In general, one will notice that the more difficult the "going" underfoot, the shorter-backed a "native" type of horse will be (and some such horses will also show a tendency to substitute the pace or a single-foot gait for the trot, to avoid the forging and striking that too short a back on too long-legged a horse tends to produce).

The Turkoman is on the whole taller than the desert-bred Arabian. This, again, may have to do with the comparative stability of footing which the Turkoman often enjoyed. Height would put Arabians in the desert at a disadvantage, as the higher one's center of gravity is over footing of any kind, the more energy is required to maintain it in balance; insecure, shifting footing takes more energy still. A taller horse under the same circumstances is likely to tire sooner than a shorter one.

In other words, the Turkoman is ideally suited for noticing, outrunning and outlasting predators, and moving to and from water, on the Central Asian Steppes; and the Arabian is ideally suited for noticing, outrunning and outlasting predators, and moving to and from water, in the Central Arabian Desert.

Among the differences which are probably due, in the main, to suitability for use and thus selective breeding, are these:

The Turkoman is often nearly mane-less. Considering that it was originally used as a "moving platform" for mounted archers, this should not be all that surprising. A flowing mane would greatly interfere with the drawing of a bow. Certainly one could braid a mane in preparation for a fight, but of course in this case one would have to know in advance that the fight was coming, which wasn't always the case. The Arabs, when they fought on horseback, used a very long lance or a short sword, with which a long mane was less likely to interfere or become entangled.

The Arabian carries its tail high when galloping, and higher than most when walking or trotting. The Turkoman runs with its tail streaming behind it, where it does not interfere with the drawing of the bow when taking the famous Parthian Shot.

In other words, the Turkoman is the ideal platform for mounted archers who shot on the run, and the Arabian is the perfect platform for lancers and swordsmen.

Among the differences which may be due, in the main, to both environmental and breeding influences -- or whose influence is unknown -- are these:

The Turkoman horse, in all its form, has a coat which glows with a metallic sheen. Not all horses in a population will show it, and some glow more than others, but as a whole, a glowing coat is a hallmark of the breed. This is due to a change in the structure of the individual hair. Many theories have been put forth as to why the Turkoman glows, but none explain why the Turkoman horses in particular benefit from this genetic difference and why other horses would not.

The Turkoman horse is narrower in the body than the Arabian, or indeed than any other breed of horse. This helps it to dissipate heat quickly, but it is also a great aid in twisting and turning in the saddle, which would be invaluable to mounted archers who need to shoot in any direction, as opposed to lancers who need a firm footing from which to thrust a lance. Lance-throwing from horseback would be far easier on an Arabian -- whose "wider wheel base" would also help with making the sharp turns that close-in fighting requires.

In other words, the Turkoman was the ideal horse for the Turkmen, and the Arab was the ideal horse for the Arabs.

So how did this confusion over which horse was which arise? There were probably several contributing factors.

One of them was that when the first Oriental horses were imported to England, it simply didn't matter what kind of horse it was, so long as it was elegant and fast and could race.

Another comes from Islam. Throughout the Islamic world in previous times, it was commonplace for Arabs to "adopt converts into the tribe," so to speak, especially if they were wealthy and/or in positions of power. A Turk who converted to Islam was taught Arabic (to read the Koran in Arabic) and called an "Arab" by the Arabs. The Turks, being nomads, were generally open to new ideas from all over the place; many who were previously Buddhist or Zoroastrians embraced Islam and thus became nominally "Arabs." Thus their horses might have gotten that appellation by association. (For more information on this process, see Frye below).

All this may have contributed to the fact that in England, as Sidney tells us, "Every Oriental horse -- Turk, Barb or Egyptian bred -- is called an Arab in this country."

How much the Arabian and the Turkoman have been crossed in the past is open to debate. There are those who believe that this was never done, on either side; and it may well be that in remote places like the Nejd the core Arabian was kept "pure," just as the Turkoman would have been kept "pure" by the most nomadic tribes of Turkmen.

However, it is very likely that there was some -- and in some cases a good deal of -- intermingling between these two types of Oriental hotblood, especially where their borders met. We know that Turkoman stallions were kept for use by the elite palace guards of the Caliph of Baghdad, and that it was these stallions which he used for breeding with his Arabian mares. It was probably from these horses that the Muniqui Arabian arose.

"Turks" and the English Thoroughbred

The idea that the Turkoman horse, in any of its many types and strains, may have influenced the English Thoroughbred in any way is anathema to many people. But this is not only possible, but very probable.

It has been argued--mainly by Arabian proponent Lady Wentworth--that all the "Turks" listed in Weatherby's General Stud Book are actually "Arabians of the highest class" who are only called Turks because they were bought or taken as prizes of war in Turkey and the Crimea. There is, however, plenty of evidence that the Turks were actually Turks (Turkomans) and not mislabelled Arabians.

The first Turkoman recorded in England is said by Marvin to have been a stallion brought over by Colonel Valentine Baker, who wished to see it used to breed with the English Thoroughbred. We have not yet come across any information as to what happened to that horse once he reached England.

Turkomans were brought to England by soldiers stationed in various parts of the East, the most famous of which was the stallion Merv, who was brought to England by Baker Pacha in the 19th century. What was so astonishing about Merv at the time was the incredibly high stud fee which was charged for his services, £85, which at that time was considered exorbitant for any stallion. Unfortunately, other Englishmen did not esteem Merv the way Baker Pacha did. Sidney quotes a correspondent who had seen Merv as saying, "He looked to me about 16 hands high, fine shoulders, good head and neck, fine skin, good wearing legs, bad feet and leggy. I thought him unsuited to breed hunters ... he looked to me about an 11 stone horse, and not like going through dirt." [A stone = 14 lb, so an 11 stone horse would be one expected to be able to carry about 150 pounds or about 68 kg.] Merv covered no mares in England, and in 1877 he was sold to the Earl of Claremont's stud in Ireland.

Turks on the Continent

Turkoman horses, aside from being occasional gifts of state, were often brought into Western Europe by various individuals, most connected with the military in some way. Some of these horses have had a profound impact on various European warmblood breeds.

During the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, one of the most universally acclaimed war and racing horses in Europe was the Neapolitan Courser. Gervaise Markham, Master of Horse to James I of England, describes the Neapolitan in terms which will sound very familiar to the fancier of the Turanian horse:

"A horse of a strong and comely fashion, loving disposition, and infinite courageousness. His limbs and general features are so strong and well-knit together that he has ever been reputed the only beast for the wars, being naturally free from fear or cowardice. His head is long, lean and very slender; and does from eye to nose bend like a hawk's beak. He has a great, full eye, a sharp ear, and a straight leg, which, to an over curious eye might appear too slender -- which is all the fault curiosity itself and find. They are naturally of a lofty pace, loving to their rider, most strong in their exercise, and to conclude, as good in all points that no foreign race has ever borne a tithe so much excellence."

Markham preferred the English Thoroughbred first among all breeds of horses; the Neapolitan second, and the steppe-bred Turk third, notice that he had seen Turks racing on English race courses. (This would have been around 1566-1625.) He also noted of the Turks he had seen that, "Naturally they desire to amble, and, which is most strange, their trot is full of pride and gracefulness."

The most well-known of these horses is possibly Turkmein Atti, (one of many spellings of this horse's name). Although a drawing of him done (presumably) from life shows a horse with many Arabian characteristics, the name is curious in that it means "Turkmen horse" in Turkmenian.